Scent of a woman

Thinking of diving into Pacino? Scent of a Woman is loud, heartfelt, chaotic—and somehow exactly what you didn’t know you needed.

MOVIE REVIEW

Shreyash Manral

7/27/20258 min read

One of these fine, ordinary days—somewhere between deadlines, emails, and inhaling instant coffee—I found myself deep in conversation with a colleague. Now, this wasn’t just any colleague. This was the PhD-certified brainiac from one of India’s big-name scientific institutes. Naturally, our chat was rooted in the intellectual mud of work and work-adjacent topics… until—surprise!—I derailed it. Because of course I did.

I casually asked him what he liked to do in his spare time. You know, as one does when one is looking to procrastinate without calling it that. For context, I’m the sort who enjoys diving into a murky puddle of OTT content, so I was genuinely curious. And wouldn’t you know it—he too was a film buff! But not the “I-watch-whatever’s-trending” type. No sir. This man had opinions. The kind of opinions formed after marinating in Scorsese, Pacino, and some other actor whose name I forgot—but who starred in There Will Be Blood, so, yeah… big deal.

Now here’s the twist: as he went on about Pacino’s performance in Scarface—which, by the way, he declared to be the finest—I had a revelation. There’s always more to discover. Just when you think you’ve seen it all, a PhD guy comes along and humbles your entire filmography. So yes, I watched Scarface. Want to know what I thought? So do I. I’m working on it, okay? Been inconsistent. But now… NOW, I promise I’ll catch up. Probably.

Anyway! Riding the wave of cinematic momentum (you know that thing where you get emotionally glued to an actor and must now see them in everything they’ve ever done?), I watched Scent of a Woman. And let me tell you—what. a. ride.

I dare say—without hesitation, without stuttering, and only a pinch of melodrama—that this is Al Pacino’s best performance. So far. Okay fine, I still have some ground to cover, but my gut tells me this one’s a winner. He wasn’t alone, though. His young co-star—whose name escapes me because I’m clearly terrible with names—was phenomenal. The chemistry, the dynamic, the unspoken father-son energy? Chef’s kiss. It reminded me of Good Will Hunting, which, I know, is a cliché comparison—but hey, clichés exist for a reason. When the ingredients are just right, the cinematic sauce simmers into something divine.

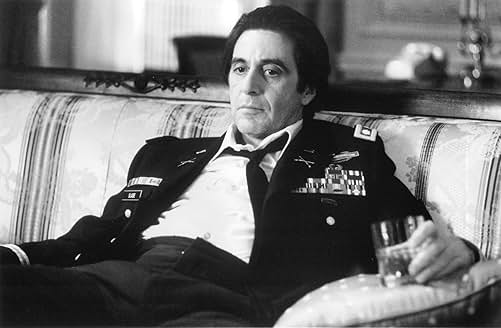

So here’s the plot, boiled down: Al Pacino plays a retired Lieutenant Colonel in the U.S. Army. He’s gruff. He’s disciplined. He speaks like every word is a command. And then there’s this shy, nervous boy—Charlie (finally, a name I remember!)—who’s on a scholarship at a prestigious prep school. The kid’s from a modest background and is just trying to earn enough money to buy a ticket home for Thanksgiving. So, naturally, he picks up a weekend gig as a… babysitter? Well, escort, technically. And no, not that kind. He’s been hired to look after this retired, blind, cigar-chomping colonel, Lt. Col. Frank Slade.

Their first meeting is... electric. Frank is all fire and thunder, and poor Charlie looks like he just walked into the lion’s den wearing a steak suit. Some might say Frank was testing him. Others might say Frank was just being his delightfully chaotic self. Either way, Charlie realizes this gig won’t be as chill as it looked on paper. Oh, and plot twist! The Colonel’s family? They’re off on holiday. Dumped the man on Charlie like a ticking time bomb in a tux.

It’s in this moment—amidst insults and threats—that we discover Frank is blind. Now, your first thought might be, “Oh no! He must’ve lost his sight in a daring act of valor!” And that, dear reader, is precisely why the actual reason hits so much harder. (Spoiler: it’s neither daring nor valorous, but you’ll love the reveal).

The next day, Frank informs Charlie that they’re off to New York. Yep. Just like that. Charlie, being the sweet, rule-following, scholarship-dependent soul that he is, hesitates. But Frank is, if nothing else, persuasive. Off they go.

During their journey, something starts to shift. Amid their conversations and clashes, you see it—that slow, reluctant bonding. Frank picks up on Charlie’s unease. Something happened back at school, something heavy. And even though Frank is practically allergic to vulnerability, he begins to care. Likewise, Charlie—against all odds—starts liking this abrasive old man. They check into a fancy hotel, head out for an even fancier dinner, and in between the jabs and jokes, something genuinely warm begins to simmer.

And then—BOOM—Frank reveals his plan. He’s in New York for one final hoorah before ending his life. Mic drop. This is where the film peels back its layers and gets real. Frank isn’t just angry—he’s exhausted. Once fiercely independent, now he can't walk a straight line without help. And help, for a man like Frank, is worse than pity—it’s a mirror reflecting everything he used to be. The shame, the rage, the grief—it’s all tangled up in this decision to end things.

Image © Universal Pictures. Source: American Rhetoric

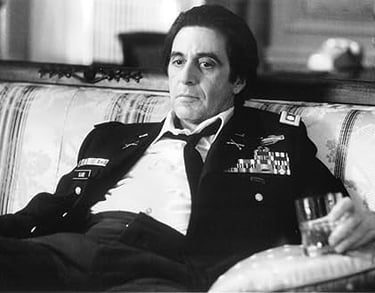

Image © Universal Pictures / via IMDb

This is when you see the man behind the act—this is a tired man seeking liberation, tired of his disability, which I’m sure he once looked down upon during his time in the army, given his ideology of being fit and perfect for the role. That’s another reason I believe he wants to end his life: he's exhausted from being helped around, from being dependent. A once self-sufficient man who could get whatever he wanted, whenever he wanted it—now finding it difficult to walk out of a room without holding someone else’s hand.

This shows up a couple of times. One such moment is when Charlie reaches out to help him, and he snaps—shouts—“I’m blind, not you! So I’ll be the one holding your hand!” That one line says it all. The frustration, the loss of control, the clinging to the last bit of autonomy. Beautiful character development, I would say. Not a complex character—you all could relate to this. Maybe someone you encountered once in your life, or someone you will. This is that kind of life default—the kind of person you’re bound to meet at some point. And I’m not taking away Al Pacino’s credit (I wouldn’t DARE) for portraying this so convincingly. His exceptional representation of a visually impaired person made it all the more powerful.

The boy, on the other hand—very subtle character enlightenment. There isn’t much you would have to wait for to understand. He is reserved, shy, nervous—all because of the situation he is in. The background, the importance of his schooling, the burden he carries on his shoulders to make himself one of those top-tier men in high-class society—that’s his dream. He thinks that’s what will make his situation better. So, his actions are aligned in the way he best thinks will lead him in that direction. The other development in this story is the bond that forms between these two gentlemen. Now that is something very beautiful to watch unfold.

The other development in this story is the bond that forms between these two gentlemen. Now that is something very beautiful to watch unfold.

You see it growing—slowly at first, almost hesitantly. One of the early moments that hints at this change is when they visit a restaurant, and Frank, in all his blind boldness, invites a young woman for a tango. It's a fleeting, graceful scene, but one that speaks volumes. Charlie sits there, watching not just in awe, but with the kind of quiet admiration that only comes when you begin to truly see someone. The dance isn’t just charming—it’s a statement. That despite everything, Frank is still a man of elegance, command, and rhythm.

Later, at dinner with Frank’s brother and family, the atmosphere shifts from awkward to tense. The family treats Frank like a burden they’ve temporarily offloaded, and it doesn’t sit right with Charlie. So, in his own quiet, respectful way, he stands up for Frank’s dignity. Frank, as unpredictable as ever, does return the favor—not with some grand gesture, but with a sliver of vulnerability. It's subtle, but it’s there. The walls are starting to crack.

Then comes the morning that truly defines their relationship—when Charlie, no longer just a paid escort, chooses to stay. He doesn’t leave, even when he could. He knows what Frank is about to do, and he refuses to let it happen. That choice—unpaid, unasked for—cements something between them. It’s no longer obligation; it’s care.

And once the storm quiets, after all the shouting, the heartbreak, the gun, and the tears, Charlie does something almost absurdly tender. He takes Frank out to drive a Ferrari. Yes, a blind man. In a Ferrari. It sounds insane—and it is—but it’s also symbolic. It’s a gift of freedom, even if just for a few minutes. A chance for Frank to feel the wind, the thrill, the control he thought he’d lost forever. It’s one of those scenes that makes you laugh a little, cry a little, and question your insurance premiums all at once.

By this stage, Frank has grown particularly fond of Charlie. He knows it, and we know it—but being Frank, he doesn’t exactly send a thank-you card. Instead, as he drops Charlie back at school, he reaches out, almost casually, to feel his face. A small gesture, barely a second long, but bursting with emotion. That’s how he says goodbye. That’s how he says, “You matter.

Image © Universal Pictures.

By now, Frank is totally fond of the kid. Deep down, he sees a version of himself in Charlie—minus the cigar and existential despair. But he’s not about to get all mushy. Oh no. He does, however, offer one of the most understated gestures of affection ever: when dropping Charlie back to school, he reaches out to feel his face. That’s it. No words, just this pure gesture. It’s not just us witnessing the bond bloom; There is yet another character in the film itself who is very observant of it, if anything, he himself happens to be an integral part of it, after all he was the one who drove them to these places. It’s obviously the limo drive I’m talking about, Manny.

Now, we’re back at Charlie’s school. The grand halls, the stiff collars, the blinding privilege. Charlie’s in trouble. Big, school-board trouble. Turns out, doing the right thing comes with consequences—especially when you don’t snitch on your equally privileged-but-morally-bankrupt classmates. The boy is being paraded before the disciplinary committee, one step away from academic doom, while his so-called guardians and school “mentors” prepare to throw him under the bus with polished smiles.

And just when you think all is lost—enter Frank Slade.

Yes, that Frank. Blunt-force-trauma-in-human-form Frank. He walks in like a grenade in a courtroom. No one asked for him. No one wanted him. But there he is, in all his cigar-wielding, gravel-voiced glory, ready to speak not for Charlie—but as the man who knows him better than anyone else in that room ever bothered to.

And speak he does.

What follows is less a speech and more a verbal artillery strike—equal parts truth, principle, and that one-liner magic only Pacino can deliver. He defends Charlie not just as a boy who did the right thing, but as a young man who has integrity—a word the school board apparently had to look up during recess. In standing by Charlie, Frank doesn’t just save the boy’s future—he reclaims a piece of his own.

Because in the end, it wasn’t just Charlie who needed saving.

It’s the perfect culmination of their journey. The boy who gave the Colonel a reason to live. The Colonel who gave the boy a reason to believe in himself. It’s messy and loud and full of flaws, like the best relationships are. But what comes out of it is something solid, something rare—a bond not forged in similarity, but in mutual salvation. And as Frank walks away, leaving the committee room behind, he doesn't need applause. He doesn't need thanks. He’s said what he had to say. Done what he had to do. And somewhere deep inside that stormy, sarcastic, half-broken man—a bit of peace finally settles in.

Hoo-ah.